Venture Capital Diversity: The Non-Obvious Solution

Venture Capital diversity has become a hot topic in recent years, as the industry faces growing scrutiny over the lack of representation among Investors and VC-backed entrepreneurs. Despite numerous efforts to address this issue, the Venture Capital landscape remains heavily skewed towards a narrow demographic, with women, minorities, and non-Ivy League-educated individuals still underrepresented. This imbalance limits the diversity of ideas and perspectives and undermines the performance of VC firms and the startups they support.

In this post, I delve into the current state of Venture Capital diversity, examine the root causes behind this imbalance, and explore innovative, non-obvious solutions that Venture Capitalists can adopt to foster a more inclusive environment. Drawing on insights from psychology, behavioral science, and industry best practices, I provide a roadmap for increasing Venture Capital diversity by addressing implicit biases, reevaluating decision-making processes, and celebrating the benefits of diverse perspectives in the investment ecosystem.

The Current State of Venture Capital Diversity

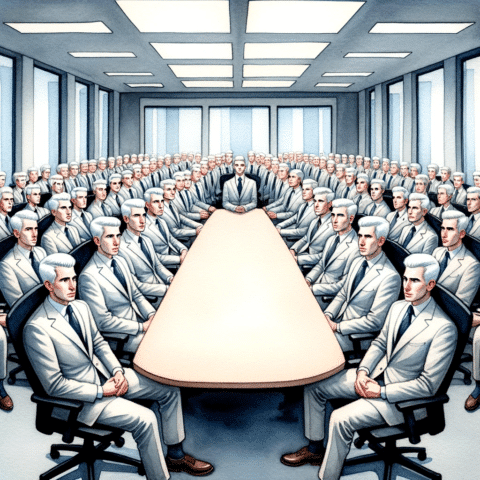

A select group of individuals has historically dominated Venture Capital. These decision-makers tend to be white, male and educated at elite institutions. As awareness has grown in recent years, corrective actions have multiplied. However, as change has been slow to occur, frustration led to finger-pointing—which is not the most effective way of dealing with biases, especially when they are subconscious.

VC Lacks Diversity At All Levels

As we evaluate the current state of diversity in VC, it is essential to acknowledge the underrepresentation of women, non-white individuals, those without an Ivy League education, and more generally different life experiences, which is hard to measure. Academics refer to these differences as endowed traits (gender and ethnicity) and acquired traits (education and work experiences).

The gender and racial makeup of the Venture Capital industry is staggeringly homogeneous.

Paul Gompers & SILPA Kovvali (Source: Harvard Busines Review)

Recent data suggests that there is still much work to be done in increasing diversity in the industry at all levels:

- VC-backed startups: According to a study conducted by RateMyInvestor and DiversityVC, only 9% of US VC-backed startup Founders are women, while a mere 2.4% are Middle Eastern, 1.8% Latinx, and 1% are Black. These proportions are far from each group’s representation in the overall population and among entrepreneurs. However, the proportion of Founders of Asian origin is close to 18%, far outweighing their ethnic representation in the US population. This is a testament to biases such as the representativeness heuristic, which I present below

- VC firms: A recent US NVCA study showed that these proportions are similar at VC firms, with Venture Capitalists being 76% White, 17% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5% Hispanic or Latino, and 4% Black or African American. One difference is that 23% of investment professionals are women (21% of investment committee members and 18% of management company owners), although other sources place that proportion at around 10%

- Limited Partners: While LPs are instrumental in promoting diversity, as they hold the purse strings, few studies have analyzed it at their level. One informal study places gender diversity at a 75 / 25 ratio in Spain. It echoes similar results from a UK BVCA study showing that women represented 35% of the LP workforce (vs. 47% of the overall UK workforce)

This lack of diversity can have significant implications for the kinds of startups that receive funding. For instance, a study by Paul Gompers and Silpa Kovvali published in the Harvard Business Review found that companies with diverse management teams have a 19% higher innovation revenue. This suggests that a more inclusive VC industry could lead to better investment decisions and a more innovative economy.

Several organizations and initiatives have emerged to address this issue and increase diversity in Venture Capital.

Efforts Made to Increase Venture Capital Diversity

A number of efforts have been made to increase diversity in Venture Capital. These initiatives can be broadly grouped into industry-level programs, firm-level policies, and individual actions.

Industry-level programs, such as All Raise, 37 Angels, and BLCK VC, focus on increasing women’s and Black professionals’ representation in the VC space. These organizations provide mentorship, networking opportunities, and resources to help underrepresented individuals break into and succeed within the industry. They also work to raise awareness of the diversity issue among VC firms and startups.

Firm-level policies, on the other hand, aim to improve diversity within specific VC firms. Some firms have implemented diversity and inclusion policies, such as blind recruitment processes, diversity targets, and training programs for staff. Additionally, more firms are now actively seeking diverse candidates for their investment teams to broaden their perspectives and improve decision-making.

Lastly, individual actions are critical for promoting diversity in VC. This includes GPs leveraging their networks to identify and support diverse entrepreneurs and LPs speaking out about the importance of diversity and taking steps to make their dollars push more inclusivity.

Most startup boards are made up of a few founders and a few VCs. No wonder you have no diversity on the board.

Fred WiLson (source: his awesome blog)

A 2020 post by Fred Wilson highlighted the need for diversity at the startup Board level. He suggested several actions, including having more independent seats held by diverse people. VCs should take observer seats to make room for these new Board members, and term limits should ensure proper rotation based on skill, not seniority. A striking characteristic of diversity-friendly propositions is that they are also good for business.

While these efforts have led to some progress in recent years, there is still a long way to go in achieving true diversity in the Venture Capital industry—and the current market reset has reversed past wins. The slow rate of progress has led to frustration, sometimes expressed with aggressivity or shaming directed toward the overrepresented majority. Extreme cases must be reproved and punished when appropriate, but such tactics may not benefit underrepresented parties long term.

Is Confrontation An Effective Way To Promote Change?

In recent years, there has been a tendency for some advocates to call out the lack of diversity in the VC sector in a confrontational manner. While this approach can generate attention and pressure the industry to change, examining whether such tactics are the most effective means of promoting long-term change is worth examining.

Academic research suggests that confrontational approaches can sometimes backfire, leading to resistance and defensiveness rather than constructive change. Psychology experiments studying the effect of confrontation on racial and gender biases found that confronted individuals were likely to double down on their existing beliefs rather than consider alternative perspectives.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (D.E.I.) training is no exception. More evidence has appeared on the effectiveness of such action, spelling doubt on the approach.

Mandatory training that blames dominant groups for D.E.I. problems may well have a net negative effect on the outcomes managers claim to care about.

Jesse Singal (Source: The NEw york times)

This is not to say that confrontation must be avoided at all costs. Social psychologists point to several findings validating a specific type of confrontation:

- Confrontations coming from out-group individuals (who don’t share the same social group as the discrimination target) are more likely to be effective in reducing biases than confrontations from in-group members

- Evidence-based confrontation, wherein specific examples or data are provided to illustrate the bias, is more effective in promoting concern about biases

- Confrontations encourage bystanders witnessing them to be more careful about their own biases, even when they have low initial prejudice

This is not to say, either, that public accountability and criticism have no place in addressing the issue of VC diversity. Active discrimination and reprehensible or illegal actions must be exposed. High-profile cases such as Ellen Pao’s proved that speaking up can catalyze change. On a different level, as I found out by coaching women entrepreneurs, the Dating Ring story is far from an isolated case. Sexual assault or racial violence must be reported.

However, once the bad apples are taken off the tree and chucked in the bin, what is the most effective way to facilitate genuine progress? My objective here is to study the deep psychological roots behind the lack of VC diversity to address them effectively, or at least offer an alternative. Naming and shaming have a place as an initial drive for change, but even those brave enough to put themselves at risk and blow the whistle recognize that it’s not a long-term strategy.

Understanding these biases and where they come from is the first step in addressing them.

What Is Causing The Lack of Venture Capital Diversity?

In the following section, I explore the role of implicit biases and the representativeness heuristic, shedding light on how these cognitive processes can contribute to discrimination in Venture Capital. By uncovering these underlying mechanisms, we can better comprehend the challenges and work towards addressing them effectively.

The Role of Implicit Biases

Implicit biases are subconscious attitudes or beliefs that influence our understanding, actions, and decisions, often without conscious awareness. Renowned psychologists Anthony Greenwald, Mahzarin Banaji, and Brian Nosek have conducted extensive research on implicit biases and their impact on various aspects of human behavior, which help better understand the lack of Venture Capital diversity.

One of the foundational concepts in understanding implicit biases is the Implicit Association Test (IAT), developed by Greenwald, Banaji, Nosek, and colleagues. The IAT measures the strength of an individual’s automatic associations between mental representations of objects and concepts in memory. By examining these associations, researchers can gain insights into the underlying biases that shape our actions and decisions in various domains.

Implicit biases are formed through personal experiences, socialization, and cultural influences. Throughout our lives, we are exposed to various stereotypes and associations that become ingrained in our cognitive processes. These biases can be reinforced by the media, education, and interpersonal interactions, ultimately leading to automatic associations that may not align with our conscious beliefs or values.

Not only are these types of behaviour and thinking external to the individual, but they are endued with a compelling and coercive power by virtue of which, whether he wishes it or not, they impose themselves upon him.

Emile Durkheim (Source: The Rules of sociological method)

The implicit bias studies by Greenwald, Banaji, and Nosek can be linked to Durkheim’s theory of social facts. These biases, often subconsciously ingrained in our minds due to social norms and shared beliefs, can be seen as social facts, which Durkheim describes as external, coercive forces that influence individual behavior. By understanding how implicit biases operate as social facts, we can develop strategies to address and mitigate their impact on decision-making.

In the context of Venture Capital diversity, implicit biases can have significant consequences. For instance, Investors may be more likely to fund entrepreneurs with similar backgrounds, experiences, or characteristics, even if this preference is not consciously acknowledged—a concept sociologists call homophily and is at the root of VC groupthink. This can lead to a lack of diversity in the types of startup Founders receiving funding and a lack of representation among Venture Capital professionals themselves.

Implicit biases are pervasive and significantly influence the lack of diversity in Venture Capital. By drawing on the research of Anthony Greenwald, Mahzarin Banaji, Brian Nosek, and colleagues, we can better understand the origins and consequences of these biases and take steps to address them.

First, we must address a critical question: Do prejudiced individuals measured by the IAT act in discriminatory ways? Critics of the test highlighted the low correlation between these two variables. I offer a potential pathway explaining how VCs’mental shortcuts may translate their implicit biases into action.

Psychological Roots: The Representativeness Heuristic

Venture Capitalists are known for looking for trends to form a point of view on an investment opportunity. They apply pattern matching to each explicit investment criterion, such as the Founders’ abilities, the startup’s traction, and market dynamics. The objective is to compare these characteristics to past examples and derive a probability of success.

Y Combinator’s co-Founder Paul Graham famously said that anyone looking like Mark Zuckerberg could trick him into getting funding. Graham said it in jest, but it is a reality of Venture Capital investing. When they analyzed Founder interviews to identify negative biases, YC’s partners found that they subconsciously discriminated by age. Few startups accepted into the acceleration program had entrepreneurs older than 32.

Availability bias played a role: the analysis was done in 2013, one year after Facebook’s IPO. Zuck was only 28 at the time. This non-characteristic example—the average age of successful Founders when they start their company is closer to 40, and only one quarter is younger than 30—was undoubtedly at the forefront of YC Partners’ mind when they made their selection.

But a more profound bias, uncovered by Tversky and Kahneman (who received the Nobel Prize in 2002 for his work), is at play when VCs make a quick decision based on a few characteristics.

The representativeness heuristic is a cognitive shortcut used to evaluate the probability of an event or the likelihood of a situation based on how similar it is to a familiar or stereotypical example. In the context of Venture Capital, this heuristic can influence Investors’ investment decisions by leading them to rely on patterns and past experiences that seem representative of successful startups or entrepreneurs.

When VCs use the representativeness heuristic, they may subconsciously look for startups and Founders that resemble their mental model of what a successful startup or entrepreneur should look like (e.g., Mark Zuckerberg). This mental model is often shaped by the Investor’s previous experiences (priming effect), industry norms (favoring groupthink), and widely-publicized success stories. As a result, VCs may be more inclined to invest in startups that fit these familiar patterns while overlooking or undervaluing those that do not.

Why Representativeness May Lead To Discrimination In Venture Capital

The representativeness heuristic is not all bad, and it has evolutionary roots that helped us get where we are by enabling quick decision-making in various situations. This heuristic helped our ancestors assess the probability of an event or the likelihood of a problem by comparing it to familiar or stereotypical examples based on their experiences. While not consistently accurate, the representativeness heuristic allowed early humans to make rapid judgments in a complex and uncertain world, often enhancing their chances of survival.

The benefits we derived from representativeness are strikingly adapted to Venture Capital work:

- Pattern Recognition: The ability to recognize natural patterns, such as the changing seasons or the migration of animals, allowed early humans to anticipate and adapt to their environment. This would have been vital for finding food, water, and shelter, as well as predicting the behavior of potential predators or prey

- Social Learning: Representativeness helped early humans identify and imitate successful behaviors and strategies demonstrated by others in their group. By emulating those who were successful in hunting, gathering, or other survival activities, individuals could enhance their chances of survival without having to learn everything through trial and error.

- Threat Assessment: In potentially dangerous situations, the representativeness heuristic allowed early humans to evaluate threats quickly based on prior experiences. For example, if a particular animal or plant resembled something known to be dangerous, individuals would likely avoid it, thus increasing their chances of survival.

- Decision-making under Uncertainty: In an unpredictable world, the ability to make quick decisions was crucial for survival. The representativeness heuristic enabled early humans to make reasonably accurate judgments, even when they had limited information or time to deliberate.

I often tell active Venture Capitalists I train through the VC Career Accelerator that what makes it difficult to fight such biases is how engrained they are in our brains through evolution.

The flip side of the representativeness coin is that it leads to nefarious outcomes. The representativeness heuristic can contribute to discrimination and the lack of diversity observed in Venture Capital for several reasons:

- Historical Bias: The tech industry and Venture Capital have historically been dominated by white males. As mentioned before, the mental model of a successful founder may be skewed towards this demographic, leading VCs to favor startups led by individuals who fit this profile

- Confirmation Bias: VCs may be more likely to focus on information that confirms their mental model of what a successful startup or Founder looks like, ignoring or downplaying evidence that contradicts this model. This can perpetuate stereotypes and limit the diversity of startups receiving funding

- Homophily: People tend to form connections with others who are similar to themselves. Since the VC industry has been predominantly white and male, this can lead to a self-reinforcing cycle of limited diversity in the startups that receive funding.

Homophily, the tendency of individuals to associate with others similar to themselves, is a well-studied phenomenon in sociology and social psychology. This inclination can be traced back to various factors, such as cognitive processes. It manifests itself in two types: status homophily, based on socio-economic status or ethnicity, and value homophily, based on shared values, beliefs, or attitudes. As we can see, Venture Capital is a fertile ground for homophily.

Cognitive biases make it hard for many to strive for more inclusiveness and diversity. Yet, as Fred Wilson advocates, efficient ways exist, such as increasing diversity at all levels. In the last part of this article, I offer a path to attack the problem at its root and promote solutions to these biases.

How Can We Increase Venture Capital Diversity?

The first step is awareness. Awareness plays a crucial role in mitigating the impact of cognitive biases on our decision-making processes. Systematic errors in thinking may lead to irrational judgments and flawed conclusions. By becoming aware of these biases, Investors can take conscious steps to counteract their influence and make more rational decisions.

I’ve discussed the importance of delaying intuition and collecting more data using existing processes in Venture Capital, such as investment committees and due diligence. I offer more practical routes here.

Don’t Neglect Prior Probabilities

Prior probability is the initial estimate of the probability of an event or hypothesis before considering any new evidence or information. It is a fundamental concept in Bayesian statistics, where probabilities are updated based on new data using Bayes’ theorem. Tversky and Kahneman argue that we should not neglect prior probabilities to combat cognitive biases. One of the most common cognitive biases they identified is the base-rate fallacy or neglect. People tend to disregard prior probabilities (base rates) when making judgments based on new evidence.

Tversky and Kahneman devised an ingenious experiment to demonstrate how individuals often neglect prior probabilities when making judgments, relying heavily on the representativeness heuristic instead. In the study, participants were provided with a description of Steve, a shy, introverted, and detail-oriented individual. They were then asked to estimate the likelihood of Steve being a librarian or a farmer. Although there were significantly more farmers than librarians in Steve’s region, participants were inclined to judge Steve as more likely to be a librarian, as his personality traits appeared more representative of that profession.

The example demonstrates that people frequently base their judgments on the representativeness of the given information rather than considering the prior probabilities (e.g., the actual number of farmers and librarians). This tendency leads to biased judgments and highlights the importance of considering prior probabilities when making decisions or assessments.

Let’s apply this concept to Venture Capital investing.

Investors spend a consummate amount of time evaluating startup Founders’ potential strengths. They often dedicate little time to each meeting—typically thirty minutes to one hour. They call it “deal flow management”. How are they able to make decisions at such break-neck speed? In a recent interview, a successful VC said he needed only a lunch or dinner meeting with a Founder to determine if they think strategically enough (start from 16’25).

To make these fast-paced decisions, many VCs rely on mental patterns to select the individuals they will engage with. The closer the Founders they meet fit into this mental pattern, the more susceptible they are to go on to the next stage.

Take two Founders: one is white, male, and possesses a computer science degree from a prestigious Ivy League university. The other is non-white, female, and has a degree from a minor university (or from a non-US education organization, or no degree at all). Which one is more likely to get a meeting with the VC firm?

How do we solve the prior probability issue in VC? One method is to encourage critical thinking and promote the practice of questioning assumptions and considering alternative explanations. Venture Capitalists should be encouraged to examine the evidence supporting their beliefs and evaluate its quality and relevance.

Another method is to build data and analytics to show that more diversity is not only good for humanity but also business. It will update existing beliefs based on new information and hopefully make VCs rely less on mental shortcuts such as representativeness to qualify their deal flow.

Publicize Data: Diversity Works

Paul Gompers, a professor at Harvard Business School and one of the world’s most prominent scholars on Venture Capital, has spearheaded research on VC diversity for a decade. In a 2018 article published in the Harvard Business Review, Gompers and his co-author, Silpa Kovvali, explore the role of homophily in Venture Capital and its impact on investment decisions. They conclude that diverse GP teams perform better: VC firms that increased their proportion of female partner hires by 10% saw, on average, a 1.5% increase in fund returns each year and 9.7% more profitable exits.

A report by WRG published in 2020 mentioned research showing diversity worked at the startup level, too. Founding teams with more than one gender or ethnicity reached 30% more returns (MOIC) than homogenous teams.

The evidence is clear: Diversity significantly improves financial performance on measures such as profitable investments at the individual portfolio-company level and overall fund returns.

Paul Gompers & SILPA Kovvali (Source: Harvard Busines Review)

My analysis of elite VC firms’ investment committees may provide clues to explain these results. Most highly successful startups operate in non-obvious areas and develop entirely new markets. Airbnb is a prime example, but so are most genuinely innovative ideas. Kleiner Perkins’s managing partner, Randy Komisar, summed up this idea perfectly when he said disruptive ideas generate dissent among VC partners. They are so new that they can’t be attached to previous ones. Representativeness does not work with disruptive startups.

Having a diverse team in terms of gender, ethnicity, life experience, and culture brings varied viewpoints. These diverse perspectives help challenge conventional thinking, encourage critical analysis, and facilitate the exploration of new ideas and solutions.

Publicizing data on the merits of VC diversity will help push prior probabilities to the front of Investors’ minds when they make go/no-go decisions. Rather than bashing them for being male chauvinist pigs, which creates animosity, we need to recognize the role of mental roadblocks, such as cognitive biases, and help overrepresented VCs overcome them. It will foster a more inclusive environment.

Racists and misogynists must be exposed; there is no question about that. But for what I hope is the large majority of VCs perpetuating the status quo unconsciously, this approach promotes empathy, understanding, and constructive dialogue, encouraging the VC industry to embrace diversity and its benefits.

Celebrate Diversity With Concrete Examples

Celebrating diversity with concrete examples can be a powerful way to create a new mental model and foster a virtuous cycle using the representativeness heuristic. Highlighting the success stories of diverse teams in the VC industry can be a positive reinforcement, encouraging more firms to embrace diversity. VC herd mentality can be manipulated for a good cause. Shifting the representativeness heuristic in a positive direction will help to create a more inclusive environment where diverse talent is recognized and valued.

Highlighting success stories like Calendly’s Tope Awotona and Canva’s Melanie Perkins, or featuring female VCs on the Forbes Midas List helps challenge and reshape existing mental models. By showcasing the achievements of diverse founders and investors, these examples create more inclusive representations of success in the industry. As a result, they contribute to changing perceptions and making diverse success stories more ubiquitous, inspiring others to follow in their footsteps and encouraging the VC community to embrace diversity as a valuable asset.

However, this path to more Venture Capital diversity is not without risk and needs a long-term commitment, a resource few possess in our click-hungry, everything-now mentality. I have experienced the backlash in my work. Every week, I post a quote from VCs in my newsletter and have observed two notable trends.

The battle for Venture Capital diversity is long-term and needs commitment beyond the underrepresented groups most affected by it. An inclusive approach, based not on shaming but on understanding deeply-rooted cognitive biases, is a practical companion to other initiatives already at work in the Venture Capital industry.

Conclusion: tl;dr

More than most industries, Venture Capital is subject to the influence of cognitive biases, particularly the representativeness heuristic. Decision-makers relying on stereotypes and overlooking valuable information, such as prior probabilities, may inadvertently promote discrimination. As a result, the potential of diverse teams and individuals might be underestimated, negatively impacting the industry’s overall performance and perpetuating inequality.

To combat these biases and promote diversity in Venture Capital, it is essential to consider base rates, which serve as a reminder that talent is evenly distributed across demographic groups, regardless of stereotypes. By acknowledging the actual distribution of talent and publicizing data on the merits of diversity, Investors can make more informed choices and support a broader range of entrepreneurs and investment professionals.

Celebrating the successes of diverse teams at both the startup and VC firm levels is another powerful way to create a more inclusive environment. By showcasing the achievements of underrepresented individuals and groups, we can challenge existing mental models and demonstrate that diversity is an asset rather than a hindrance. As more diverse role models emerge, they inspire others to pursue their dreams.

Addressing cognitive biases like representativeness requires a multifaceted approach. Taking into account prior probabilities, publicizing VC diversity data, and celebrating diverse teams’ successes are all essential steps in creating a more equitable and high-performing industry. By embracing diversity and challenging our mental models, we can unlock untapped potential and pave the way for a more innovative and inclusive future.